Nov. 20, 2022

Today is Meredith Monk’s 80th birthday and I’m celebrating by digging into the new box set of twelve albums she’s released on ECM, and digging up this interview I did with her forty years ago.

I first encountered Meredith’s work among the initial batch of albums released by the Lovely Music label. I had read reviews of them in the Jan./Feb. 1979 issue of Synapse and was enticed to mail order Robert Ashley’s Private Parts, David Behrman’s On the Other Ocean, and Meredith Monk’s Key. I had never heard of any of them and didn’t know what to expect, but the review made them sound compelling, and I was not disappointed. In fact, all three remain vital touchstones for me. I was drawn to Meredith’s album by the description of it as “invisible theater” – not that I knew what that meant. Later that year I saw her perform the theatrical piece The Plateau Series at UCLA and was equally confused and captivated.

Meredith and her Vocal Ensemble came to Olympia to perform at The Evergreen State College on January 20, 1982. The concert consisted of the solo and group pieces recorded on her recent release Dolmen Music, and the forthcoming album Turtle Dreams, along with her short silent films Ellis Island and Quarry. (Read a concert review from the Cooper Point Journal, Jan. 28, 1982.)

I was writing for OP Magazine at the time and was thrilled when Meredith agreed to meet me on the day of the show for an interview. We had lunch at Fred’s, a venerable blue-collar diner out near the Port of Olympia. We talked for a long time and I felt good about our conversation. But when I got home and went to transcribe the tape I was horrified to find that the batteries in my cassette recorder had just enough juice to keep the tape moving, but not enough to actually record beyond the first few minutes. The sound grew increasingly distorted and faint until it just disappeared entirely. Thoroughly mortified, when I saw Meredith at the gig that night I told her what had happened. Much to my astonishment, she offered to do the interview again the next morning before she left town. That’s just one example of how gracious and kind she’s been to me over the years.

That second interview (quite heavily edited) was published as the cover story of the M Issue (Sep./Oct. 1982) of OP Magazine. What appears below is both the little bit of the first interview that was salvageable, followed by a minimally edited version of the second interview. In retrospect, I find it somewhat embarrassing, not only because of the tape recorder incident but because my questions were so utterly banal. I was 22 years old and too ignorant about her work (and everything else) to know what to ask beyond the obvious. I really had only the vaguest knowledge of what Meredith was doing or her place in the artistic firmament. So it’s humbling to revisit my clueless younger self. But I’m also so moved by her generosity and openness and patience with this adolescent fanboy.

Speaking of humility and generosity, there’s one thing I still remember clearly from that first lost interview. Meredith told me, “My sister is actually a much better singer than I am. I’m just a hard worker.” Her point was that being an artist isn’t just about having talent, it’s about showing up to do your work in spite of being aware of your own shortcomings. To this day, I try to keep that in mind and remain grateful for her wisdom.

First Interview – January 20, 1982

Do you ever think of your work in terms of folk music? Do you consider it folk music in a way? I mean, you don't improvise, right?

MM: Well there's always room within the forms to improvise, yes.

But do you have notation?

MM: Some notation, but it's usually written after the piece is done.

I'm just trying to get a feel for how much of teaching the pieces to the performers…

MM: Oh, you're talking like "folk" meaning in terms of the oral tradition?

Yeah.

MM: Oh, very much that's what it is, yeah.

So it's not like you've got these scores and people are looking at them.

MM: No, uh-uh. It's funny, because I was on a panel one time, a music panel for grants. It was a terrible nightmare, but one of the big arguments on this panel was that one person wanted to just look at people's scores and give them grants according to their scores. And I just said, forget it! And there were also some jazz people on the panel too, so the three of us just started yelling, saying that our music was much more from an oral tradition and it just made no sense to look at someone's scores.

Do you rely very much on grants to get done what you need to do?

MM: I did for a while, but now it seems like I'm doing more and more just working, and touring and that kind of thing, and that's how I'm surviving. It's very difficult to think in terms of surviving on grants because you always get locked into something that doesn't make any sense at all. Like, you have to apply two years in advance, and then by the time two years go by you're not even interested in that project you thought you'd be interested in two years ago. It just doesn't make any sense. It has nothing to do with life. Last year I had a very bad debt situation, and I really worked it off by doing solo voice concerts. And in a way it was very difficult but at the same time it was satisfying, that I knew that by my own labor I could earn my living.

Do you like touring with the ensemble, or by yourself?

MM: It's much nicer with the ensemble, it's much more fun.

It seems to me that you're dealing with emotions a lot in your music. Do you think that's dealing with emotions on a very extended and abstract level? Or do you think that it's dealing with them on a really essential and primal level?

MM: Oh, I think it's at a very essential and primal level, and abstract as well. But I think the main thing — I was talking to someone in Seattle yesterday, and we were talking about what's the function of doing art nowadays, and sort of doing, like, agit-prop political theater. And one thing I think that you can do, at least from my point of view, is that you can offer people very intense emotional experiences for two hours, and in a sense it's an affirmation of the fact that we're still human beings. I think that's about all you can do. Or, offer your ideas and solutions to what you think's going on now. But I think maintaining the fact that we're human organisms is still a way of making a positive statement in a time like this. And I think that one of the things that's going on in this time is the emotional palette is shrinking. That's as much as I feel I can do.

I ask because a lot of people, I think, seem to look at your work as if it's some sort of very obscure, far-out thing, and to me it seems very simple and…

MM: Yeah, it's very direct. Especially with music, you know, music is extremely direct.

[tape becomes totally unintelligible]

Second Interview – January 21, 1982

I’m interested in your films, that was a new thing to me. What do you want to do as a film director? How much more do you want to do?

MM: Well, I just finished doing a half-hour version of the Ellis Island film for German television. It had some color footage as well as the black and white footage that you saw, and some more black and white. That was a very interesting thing to work on, because to do a half-hour form in film, which is basically a non-narrative form – I’m not really doing narrative film, I’m doing a poetic or musical kind of film; you could say that it’s musical because the images are put together in a very musical way. A seven-minute film is one thing, but a 30-minute film is very difficult. It took me a lot of work to do it, and it’s something that is still very interesting to me. I think it's successful in that half-hour version.

I enjoyed it. Are you going to keep making silent films?

MM: Actually, the half-hour version of the seven-minute film that you saw has a soundtrack. We showed the seven-minute version on WGBH in Boston, and we did put a little track behind it. A little bit of singing, a little bit of music, very spare but still a track. So it can be done that way. But in this concert I like to show the film silently so that your ears get kind of washed out and they’re freed of the music for a while. You’re using just your eyes, and then you can go back to the music fresh. So there’s a kind of function to the films in this concert. I think that people have lost a kind of poetry about film, and they’ve really lost the musicality of images. Images themselves have a kind of musicality to them, and in a way you could say film now almost disregards images as the main medium of communication. It still is very verbally-oriented. So I really like that you can really look at something and get something from it.

Is this something that's been developing for a long time?

MM: Yeah, I've been doing these little films for years, yeah. Lots of short films.

Do you show them regularly, like at concerts…?

MM: No. [laughs]

Any ideas for bigger film projects?

The thing that was odd about working on the Ellis Island film is that since I’ve been working with the large theater or opera forms, in a way you could say that my live work is very cinematic. You know, people have always said, You should do film. Your work is so cinematic, and so I thought it was gonna be so easy to do this half-hour film. And because I understand the language of images I thought it was going to be very easy. And it’s not, because film is another language. The images in film are a different set of images than the images in theater. So it was very difficult, but very interesting. It’s a completely different form. It’s something that I want to very much get into as I go along. When I was cutting that seven-minute film that you saw I was realizing how close it was to writing music. And in a way, you could say that on an eye and ear level, film is the purest — I mean, you’ve got pure visual form, and then if you do a soundtrack you’ve got a pure aural form, and in a way that’s the purest way you can deal with images and music.

Maybe we could talk about The House a little bit, what The House is, and how it got started and your involvement in it.

Around 1969 I was teaching some workshops, and there was a very good group of people in that workshop, and we were starting to get some engagements. We did a piece at the Chicago Art Institute, and we did a piece at the Smithsonian Institution, the big museum. So it seemed appropriate to form a group and so we did, and that's The House. And in those days I was doing very large pieces for big choruses of people moving and singing, like eighty people. But we would pick those people up at the places we would go. There'd be a core group of about eight or nine people, and then there'd be sixty or eighty other people in the places that we'd go. So that's how the group started at that time. And then there have been a lot of people I’ve been working with for many years. People come and go, to do things that they need to do for themselves. But it's still kind of a network group. I know I can call upon people if I need them at any time. So it's been nice, and people are pretty close to each other. As Lanny Harrison says, The House is also a series of apartments all over the world. [laughs] A lot of apartments. And now because of the grant situation in America, it's turned into a non-profit thing, and it's now a kind of clearinghouse for other activities. Within the House Foundation there's The House, which is the company that tours the large pieces. Then there's a repertory touring company, which tours smaller pieces and without me. Smaller movement and music pieces, but not the concerts. And then there's the vocal ensemble, and we tour the concerts.

Earlier we were talking about scores, and trying to work with other people and teach them your techniques. Do you have a way that you've sort of codified all this stuff, so that you can go to another town and pick up people and make it easier for them to learn it?

MM: Well, I don't think I can do that so much anymore because I think what I'm doing technically is too difficult. But I’m not really a person who’s very much into codification and systematizing a situation that's basically music that comes from a completely different place than systems. There are other people working that have done that, and that’s much more acceptable to your normal person. Like if you codify something or make a system then you’re okay. But I just don’t believe in it, I think it’s a bunch of bullshit, myself. Having seen someone like [Martha] Graham, for example, in dance, who in a sense was discovering a vocabulary, and you get the feeling that when she was working in the early days — I had a teacher at Sarah Lawrence who had worked with her when she was first starting to work, and you got this sense of excitement about working on — like, they'd spend a month just working on falls. Can you imagine that? Just discovering and working. And then when she finally put it into a technical code, the work stopped as far as I’m concerned. Myself, I want to just be a very fluid worker, and I want to be always growing and changing. And I think that once you can put it into a system you’ve already killed something. But I know that it’s much more acceptable to the powers that be. People think that it has validity because it’s been put into a system.

I wasn't really thinking of it in terms of that, but more in terms of trying to communicate it to other performers, to make it easier for them.

MM: I think that it can be done in a much more direct and more physical kind of way, where it’s basically a one-to-one situation. It’s done in rehearsal or workshops or whatever, and I think people pick up on it, it’s something that can be conveyed, yes. I mean, there are techniques that can be taught, sure. Exercises, textures, all kinds of things that can be transmitted.

It just seems like once you start building up a large vocabulary like that, you must have to start finding names for things – the “warble”, or the “high-pitched staccato scream”, or whatever you want to call it.

MM: But see, the other thing that's interesting, I think, about the voice and working with other people, is that everybody’s voice is different. I remember reading this old article by [Fedor] Chaliapin, who's that great opera singer in the beginning of the century, the Russian singer. It was in an old music magazine that I read from 1905 or something. And he was talking about trying to find a singing teacher, and that every throat was different. And that's true. Like you could have something that you think is a technique, and then if you teach it to somebody else it’s gonna sound different. They’re gonna have their own way of doing it, or their own technique. And so it’s a balance between those two things. I mean, I can teach how to find glottal break, and how to extend range, and slides, and different ideas, different textures, like how to get two notes at once. All kinds of things like that. I can teach my music to other people. Like Naaz [Hosseini] and Andrea [Goodman] know Songs from the Hill, but how they do it is going to be completely different. And I accept that because I know that I’m working with a live instrument. I’m not trying to get people to sound exactly like me.

Do you enjoy teaching?

MM: I do, yeah, I enjoy teaching. I don't teach so much anymore because I don't really have an awful lot of time, and if I'm gonna put my time into something I'd rather put my time into new work, and composing, and rehearsing. But I do like teaching, I just don't have the time.

It seemed like last night Gotham Lullaby was really fast.

MM: It was? I think it's just because on the ECM record it's very slow. [laughs] After I had recorded it, and I went back and heard some old renditions of that lullaby, I realized I had taken the tempo very slow. I was wondering why I was having so much trouble with my breath! I'd go, God, I don't have enough breath to finish this phrase! I never remember having this much trouble with the breath. And I realized that my tempo was so slow!

That was a lot of fun last night.

MM: Yeah, it felt great. The first set felt real good.

There were some people behind me saying, "I wonder if she's gonna do Dolmen Music? She can't possibly do all of it, I mean, how could she do that?"

MM: Well, we did! [laughs] Dolmen Music is a lot of fun to sing. It's real fun. Really, this is a really nice concert. It's one of the nicest concerts to do. If I'm singing Tablet and Dolmen Music — you haven't heard Tablet but if I sing Songs from the Hill, Tablet, and Dolmen Music, I'm dead for two weeks or something after! I'm just gone. Tablet is so difficult, and Dolmen Music. But somehow this concert's a really nice balance of highs, lows, this and that, so you're not — you're exhausted, but it's not like you can't sing for a few days. And the films give you a rest. And it's got a nice combination of humor and seriousness. Turtle Dreams is a lot of fun to perform, and then Dolmen Music is sort of like opposites. And so it's just a nice thing to do, it's a real nice concert.

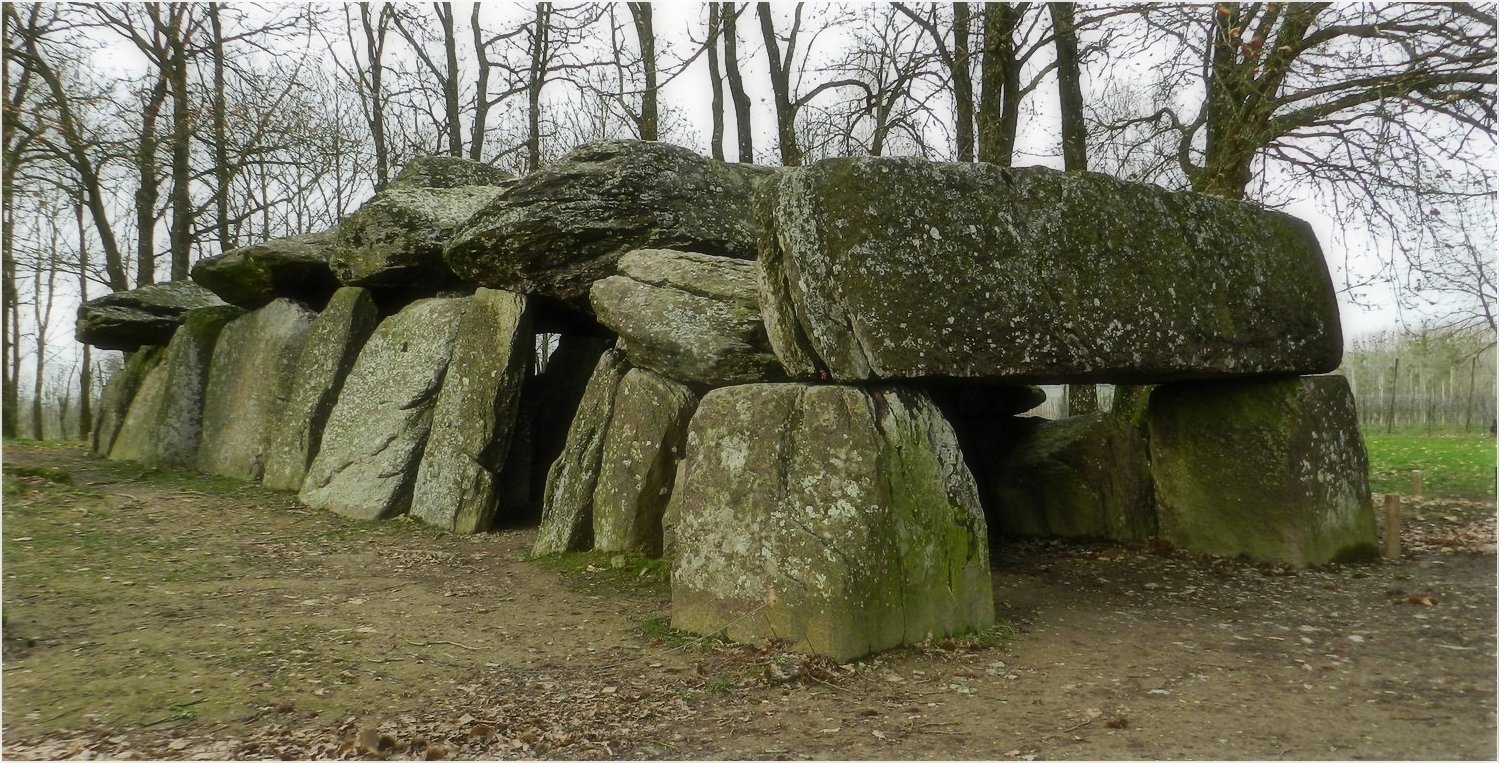

Does mythology play a very big part in what you’re doing? Like in Dolmen Music, the whole mythology surrounding those structures?

MM: Not really. Not "mythology" like verbal mythology, like that I've looked up all the stories about the stones. No, not at all. The more I work, the more I realize that I really work best from direct experience. Somehow, having experienced those stones, it was just amazing. It was like some kind of energy field inside those stones and around them. They were just in the middle of nowhere. I mean, we're just driving down this road in Bretagna, seeing all these farms and gas stations and everything, and all of a sudden – BOING! – just on the right are these stones. It’s just incredible. You get out and you can just feel — it’s like an energy field, that’s the only way I can describe it. It's called La Roche-aux-Fées, which means the Fairy Rock. And about a month later I went and visited some friends in the Lyon area, in the middle of France, and there were another set of stones. They weren’t dolmens, but they were the same kind of stones. And you could feel it again. It’s very, very strong. And so it was really from that experience that I did Dolmen Music, not looking up mythologies. I’ve tried working off things that I’ve read and that kind of thing, and I never do well. It’s always much better if I’ve had a real emotional experience. Like when I went out to Ellis Island, it was a very strong experience. And that's how I worked on the film, it was very much from that experience. It’s right in New York Harbor, where the immigrants came at the beginning of the century, on the East Coast.

It'd be great to perform Dolmen Music at the dolmens.

MM: Yeah, it would. Although outdoors it's always hard to sing, and the acoustical thing is very difficult.

Do you think much about how music relates to specific places? Like, does a lot of your work come out of that? Do you ever want to leave things there?

MM: Oh, yeah. Songs from the Hill definitely came from being in New Mexico, no question about it. And Dolmen Music comes from being in Bretagna. And I think that all of my music has kind of a "landscape" quality to it. In a sense you could say I'm trying to do "vocal landscapes," and I think that’s pretty much what I’m doing.

To what extent do you like to fill in the story?

MM: What story?

Well, say in Turtle Dreams...

MM: What story? [laughs] I think Turtle Dreams is much more a kind of atmosphere of urban alienation and urban angst, and pre-nuclear war angst, and post-nuclear war angst. It also has a slightly German, Brechtian quality to it, which I want. A sort of German pre-war feel to it. So I think it’s just more like creating a certain kind of emotional atmosphere, but there's not really any story line at all, it’s all form. It's slightly rock and roll band, slightly black soul group. It’s got a lot of stuff in it.

Does that same thing hold true for some of the early big things that you did, like Education of the Girlchild? Or did that have more of a “plot” to it?

MM: Well, they never had plots, but that was, you could say, a more theatrically-based piece, whereas this is a more musically-based piece. You have the movement or the imagery coming right out of the music, whereas with Girlchild the images came first and then I wrote the music. That was not a plot, but it was a kind of mosaic or mythic — it did have a scent of myth, not “mythology” but myth, of this group of women, and each one very unique. And then the one person’s life in the second act. But I mean in very general and archetypal terms. It was not a story line at all. Again, a much more poetic form. I’ve never been able to tell stories. I’m not a good storyteller, I’m terrible.

How do you feel about doing things that are older pieces for you? Like Biography and those kinds of things? Is that tough, or like a duty for you?

MM: No. Sometimes I've thought, If I sing this again I’m going to totally flip out, I can’t handle it! But it kind of comes and goes. In some ways, I’m singing them better than I used to, and if I still feel like I’m creating every time, still exploring, then it feels fine. If I’m not, if I’m just holding onto things that I think work, then it’s not good at all. I’ve been feeling very good about singing these things now. You bring what you have at the moment to a form, and as long as it’s not mechanical, you’re still growing and trying things. You've gotta have the courage to let go and just keep on working and finding things. I have some new music now that we're doing for Specimen Days, but I haven’t really worked on it enough to do it in concert form yet. I have to rework it into a concert format.

Do you want to talk a bit about Specimen Days?

MM: What would you like to know about it?

Well, I don't know anything about it because, hey, I live in Olympia, Washington, ya know?

MM: Lucky you. [laughs]

In New York they may know all about it, but those kinds of things don't reach us. I didn't even hear about it until about a week ago, someone mentioned that you were doing this sort of opera thing in New York.

MM: I'm amazed you heard about it at all. That's great! News travels! Well, it’s a kind of opera form or musical theater piece that we’ve been doing at the Public Theater, and it was produced by Joe Papp. It has some Civil War imagery in it, and it has some very contemporary and kind of futuristic imagery in it. And very much about, again, like, pre-World War III. There’s one scene with these miniature tents on stage, and these gigantic cannon balls mow them down. That's one image. And there’s another very funny scene with two Abraham Lincolns, but real fake looking, I mean a fake beard that's just pasted on. And then these walking trees. One's summer, it's a tree that has little flowers on it. One's a tree that has pine needles on it. You know, trees of three seasons walking around. And then there's a telegraph operator. I mean, it’s very abstracted. There’s a Northern family and a Southern family, and they have eating scenes where they eat completely differently, totally different gestures, as if you were looking at two cultures side by side. It’s very anthropological in that way. And then it has some very futuristic scenes in it. Part of Turtle Dreams is in it, just a little excerpt. And there’s a very funny film that I shot of this turtle – I have a turtle, I like turtles very much – and I shot a film of this turtle in a swamp, that's the first time you see the turtle. Then the second time you see the turtle is in negative, so you see this white ghost turtle walking across a map of the United States. And then the third film, I had this miniature city built, so you see this turtle like Godzilla in a city with nobody there, and the sand, as if the neutron bomb had fallen or something like that, and there’s no one left in the city but the city itself is totally intact. And then the turtle looks up to a moon and in the next shot the turtle is on the moon, and then the last shot you see the turtle walking towards the moon and you see the Earth, and that's the end of the film. So that goes through the piece. It’s just an exploration of how during the Civil War there were certain impulses that started, a kind of mentality. Well, that’s always existed, like This person’s a female, this person’s a male; this person’s black, this person’s white; this is the North, this is the South – all that kind of dialectical thought process, and how that goes up until now. It’s not done in an intellectual way, it’s done visually, so you know there are these impulses that still exist, and that situation of human folly still exists. And that’s what the piece is about.

Are you nostalgic?

MM: I’m not really nostalgic. In a funny way the Civil War period doesn’t interest me too much. I just started getting interested in it because I was spending a lot of time in Europe, and I was realizing that Europe had gone through two world wars on their soil, and that it really influenced them and us, and that we as a people have not had anything hurt our land, except for natural disasters. But we haven't had a people come and roll over our land the way that Holland has, and Belgium has, and France has. And so I was fantasizing, you know, wondering how Americans would be able to hold up to that. I mean, we’re strong people, but we’ve had life pretty easy. So then I naturally went right to thinking about the Civil War, how that was the last war that was on our soil. And that's how I started getting interested in it.

To me there seems to be a certain amount of nostalgia, but not just in those kind of past images but also in the images you’re talking about in the future too. It’s a sort of sad looking back on the neutron bomb or whatever it is that happened.

MM: The future, yeah, right. I mean, it's sort of like looking at the Earth from a Martian’s point of view, a real sort of cosmic overview of human frailty and compassion. But also I think it has a lot to do with what we talked about yesterday, which is about that nowadays, it seems, if you have times like this, you wonder what the function of being an artist is at all. I spent a lot of years, maybe the last four or five years, thinking that doing art just didn’t mean anything anyway. You know, that it was just a stupid thing to be doing and pretty meaningless in the scheme of things. And what’s the function? Because mostly, people are just doing art to get famous or whatever their satisfactions are. Money, or this or that. It just doesn’t have much actual function in this society. And I think that the only thing you can offer is, like, some kind of affirmation of what it is to be human now. And that comes from however you do it. It might be that it comes from, if you’re a person that's very political, doing a piece that shows people what’s going to happen if there are all these nuclear plants, and then they can do something about it. I mean, if you’re that kind of an artist. And that the artist still is a kind of antenna or society's conscience in a way. So for me, if I can offer people a very extreme emotional experience in a two- or three-hour period, that affirms that their emotions still exist, that’s what I can contribute. So maybe that’s why I like doing the music.

Did you ever come close to quitting doing this?

MM: Well, I was kind of depressed for a few years. I don’t think I could stop. I think it’s just so much part of my life that I don't think I could stop even if I wanted to, but I was feeling pretty bad about what I was doing here. See, when you really realize that you’re just part of something, and you realize after a lot of trials and tribulations — because I’ve been working for 15 or 16 years, and most of my life has been devoted to my work. I haven’t had much of anything else in my life. And then you start realizing that in a sense the thing that makes you work is the joy in the work itself, that that’s really what it’s about. You could just go through every single thing that’s ever happened to you in your life – like, you've had recognition, and da-da-da-da-da – you can just go from one thing to the next thing trying to figure out what it is that you’re doing, and all those things can be taken away from you. Everything you get can be taken away from you. It’s so completely ephemeral. But the working itself is the thing that really is the joy, and nothing else means much of anything. Because, say you get a good review or something like that. A lot of people base their whole careers on the fact that they get good reviews. And do you know how many minutes it takes for that to be over with? About ten minutes, and that’s it. It’s like maya or something, it's illusion. Then the person gets a bad review the next day and then they have that pain to deal with. So all of that is not really important at all. And so then it feels okay, if you realize that it’s moment by moment and working is working and that’s what it's about, then it feels okay. And when I finally came around to that, then that “achievement” was not meaningful. In other words, what I was going through was a kind of crisis of realizing that I had been devoting my life to something, and that the achievement aspect of it was not that meaningful. That you could go through a whole life and go, I did this, I did that, I played here, I played there, I did this piece, I did that piece and so what, you know? I mean it doesn’t mean anything. But the day-to-day work is still meaningful.

So then for you, where does the performance aspect fit into that scheme of things?

MM: I love to perform. I feel like it’s a real giving thing. It’s a real exchange. That’s the best thing about it. Like the audiences that we've had on the West Coast, it’s pretty hard to do a bad performance for them. We've got so much energy. I mean, we were just doing six weeks in New York of Specimen Days with these audiences just sitting there like, show me, do this, do that, just struggling. And even though it's a very successful production and we're running another three weeks and blah, blah, blah, like on the level of New York it's very successful, but we'd be sitting with those audiences every night — not every night, because sometimes there'd be something going on in the audience — but it's basically a very "show me" kind of attitude. So we're doing our best, keeping our energy up, that kind of thing. Six weeks go by, we have two days off, and then we're on this tour for three weeks. And everybody's going, Oh man, I don't think I can do it, and we're exhausted. So we go into Seattle and the audience — I mean, I just walked out and there was so much love in that audience, I was just flying. I couldn’t do a bad performance for them. It was so wonderful. And so that was very meaningful. You know, it's an exchange of love and energy. I know it sounds very cornball, but it’s true. It’s a giving thing, and any performer who doesn’t know that is not a good performer. You’re there for them, you're not really there for yourself.

It's true. I was talking to a friend of mine about, "Why are we bothering to do this?" And I think it comes out of really wanting to share this incredible thing that’s so meaningful to you with someone else and wanting them to maybe understand how it makes you feel.

MM: Yeah.

I run into a lot of people, especially In rock music – sometimes I just really wonder what they're doing it for.

MM: That's why they don't last very long. You know, you can't sustain that for very long unless it really is a thing where you are giving. I don't feel like you can sustain a whole life of doing it unless that's what your first thing is. That's why the rock thing, it goes very fast. We did Turtle Dreams last year at Bond's Casino in New York, which is this great big rock casino. It was for a benefit for the Kitchen. And we were like the big hit there. We had hand mics and everything, we were functioning in that rock and roll situation really well, we were like the hit of the evening. And everybody in the group, it was like all their fantasies — everybody was going, Oh boy, rock and roll stars! Fantasy fulfilled! But it was so easy to see that that atmosphere, it's just so hard to sustain. And that's why I wouldn't choose to do that. It's just very difficult. I mean, when I was in the Inner Ear, when I worked with Don [Preston] and I hung around with the Mothers a lot in those days — Don was a good friend of mine and I was in some of Frank's [Zappa] films, and that kind of thing. I was doing my own work at that time so I knew the difference between those two worlds, and I just saw how the rock thing — I mean, I think rock is great, I love rock and roll, but I really see what it does to a human being, and it just depends on what you want to do. Because if you want to be working for a few years, it's great. But if you want to really sustain your work process I think it's awfully hard to do that within the rock context. I mean, the Stones are incredible, that they could be working so long. But I don't think it's easy. It just eats you up. I mean, at Bond's we were just screaming our lungs out, and a lot of the subtlety gets lost. The energy rush is great but you just see that the atmosphere, you could just be wasted in no time at all. Like Patti Smith, she just split, you know? She probably just wasn't growing, she just couldn't do it. Which is smart, I think she's smart. She'll probably come back, though. I bet she will. I think she's an artist.

Do you find that audiences have a better idea of what’s going on with your music now than maybe ten years ago? Or do you think that they’ve always understood? Or that they've never really understood?

MM: On the level of understanding, I don’t think there’s anything to understand, number one. “Understand” is always a word that I have a lot of problems with, because it always has to do with the fact that you’ve thought it through on a kind of intellectual level, and it always implies a kind of distance to me.

Maybe the word I’m looking for is “accept” rather than “understand.”

MM: I think that the music's always been very direct on a feeling level, and I think that’s why we tour easily to Europe. We can go anywhere, because there’s no language problem. I mean "language" in terms of verbal language and in terms of image language. It can go anywhere. So that’s why we’ve had an easy time with the music. And I think there have been people who’ve gotten the emotional connection all along. But maybe there are just more people now listening to it. It seems real simple to me. I just never understand — and there’s that word, “understand”...